2024 Japanese Grand Prix: Selected Tyres – Formula 1 returns to Japan just over six months after its last visit to the country. This year, the Japanese Grand Prix takes place in April for the first time in its history: right up to last year the race was always scheduled for the second part of the season, in September or October. As a result, Suzuka has frequently crowned world champions – both in the drivers’ and manufacturers’ standings. The last two years have been no exceptions: in 2022, Max Verstappen sealed his second title at the venue, while last year Red Bull were crowned constructors’ champions.

The fourth event of the season coincides with the peak of the cherry blossom – or Sakura – season, between the end of March and beginning of April. It’s also the very first time that the Japanese Grand Prix will be held at this time of year: the first Pacific Grand Prix took place at Aida on 17 April 1994, before moving to October in 1995. The early spring will also bring lower temperatures than the teams are used to in Japan, with average temperatures ranging between 8°C and 13°C.

Suzuka is a true classic: the 5.807-kilometre Honda-owned track tests every driver’s talents with a demanding layout characterised by a figure-eight layout, unique in Formula 1.

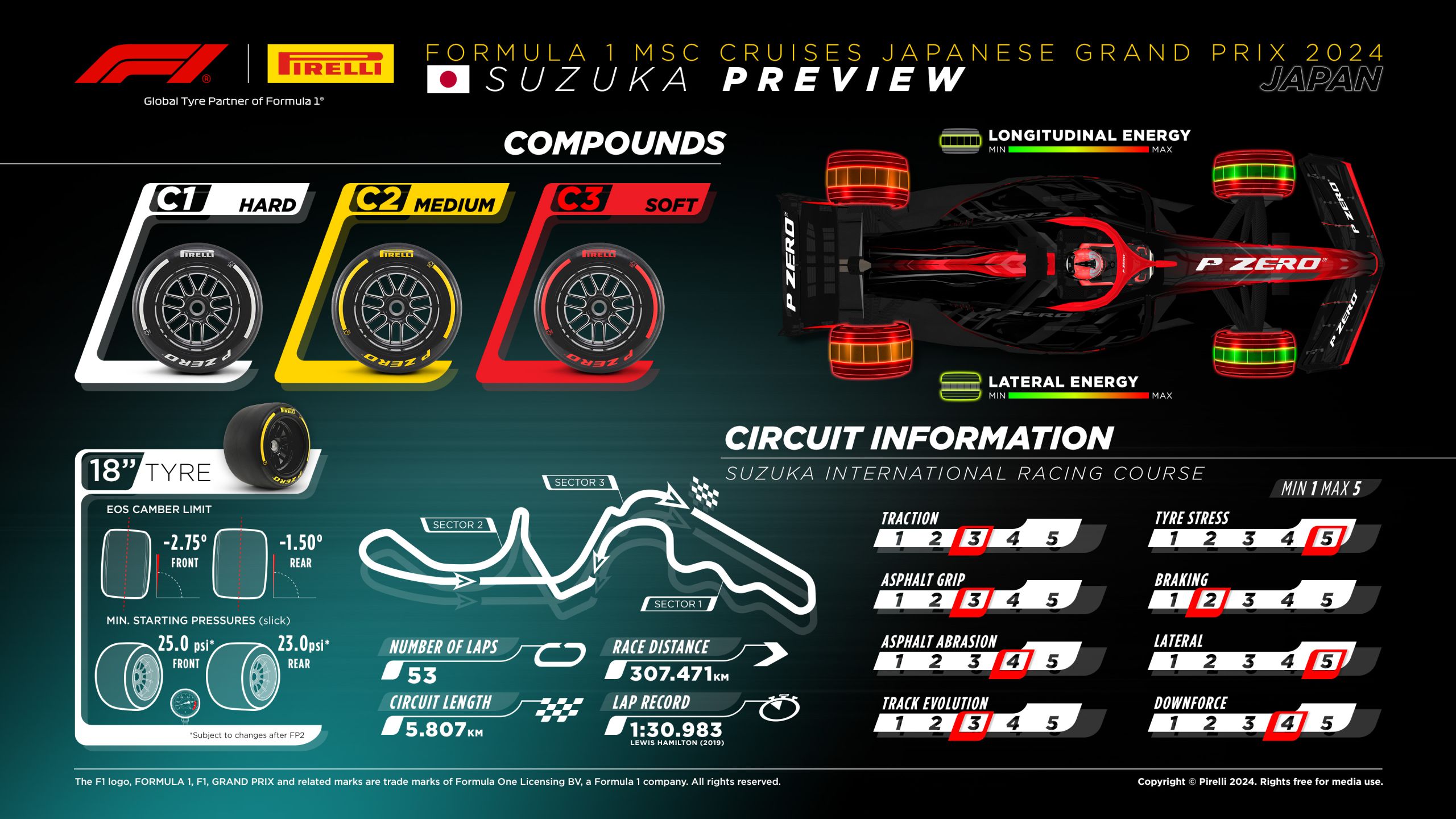

In addition to representing an extraordinary challenge for cars and drivers, the track also tests the tyres: both in terms of wear – due to high levels of asphalt roughness and abrasiveness – as well as through the forces and loads to which they are subjected throughout the variety of corners that make up the lap. As usual, Pirelli has selected the hardest trio of compounds: C1 as hard, C2 as medium and C3 as soft. This is the same selection as was used in Bahrain for the first race of the season.

A two-stopper is the most common strategy, due to the energy going through the tyres and the stress to which they are subjected. However, lower temperatures might mean that a one-stop strategy becomes possible, especially for drivers who are gentle on their tyres. On the other hand, this might make it harder to keep the tyres in the correct operating window, particularly when bringing them up to temperature on an out-lap from the pits. A one-stopper also decreases the effectiveness of the undercut, which is usually very useful at Suzuka, even with the hard and medium compounds being the preferred race compounds.

After the Japanese Grand Prix there will be two days of Pirelli tyre testing on Tuesday 9 April and Wednesday 10 April with Stake F1 Team Kick Sauber and Visa Cash App RB Formula One Team, to develop constructions and compounds for next season.

There have been 37 editions of the Japanese Grand Prix so far, 33 of which have been held at Suzuka. The remaining four took place at Fuji track, which is owned by Toyota. The most successful driver is still Michael Schumacher with six wins: the German also has the most pole positions (8) and podium finishes (9). In terms of team achievements, McLaren has the most victories (9) while Ferrari has the most pole positions (10).

The Suzuka circuit has 18 corners, some of which – such as Spoon, 130R and the uphill combination between Turns 2 and 7 – are among the most famous on the world championship calendar. Less well-known are the two Degner corners, named after Ernest Degner, a German motorcycle racer of the 1950s and 1960s.

Born in Gleiwitz (in Poland’s Silesian Highlands) in 1931 and raised in East Germany, Degner was one of the most prominent sportsmen in Eastern Europe. He raced MZ two-stroke motorcycles designed by Walter Kaaden: a brilliant engineer who worked for the Nazis at Peenemunde during World War II: the secret weapons research facility commissioned by Adolf Hitler. Thanks to Kaaden’s creativity, the MZs were able to beat not only the established European competition but also those of their emerging rivals from Japan, who were just beginning to make their name.

In 1960, for example, Suzuki entered international competition for the first time but the Japanese bike was dramatically slow, finishing the 1960 Isle of Man TT a full 15 minutes behind the winner. It was clear that the Japanese firm urgently needed external know-how, but where to find it? The answer came in the form of a chance meeting that took place the following year between Degner and company president Shunzo Suzuki. During their conversation, Degner said he was tired of his dull life in East Germany, as the rest of the world was starting to emerge from post-war austerity: he had also had enough of the constant surveillance from the Stasi – Germany’s secret police – who followed him to every race.

The Stasi were so concerned that Degner might defect that his family weren’t allowed to come to race, so that he would always have a reason to come home. Naturally, Degner also hated the fact that most other riders – even those with far less talent – were paid much more than him, as under his home regime he had to settle for a salary equal to virtually any other MZ worker.

An agreement was quickly reached: Degner would run away, help Suzuki develop their bikes and then race for the Japanese. But he wouldn’t leave East Germany without his family and, with the Berlin Wall having just gone up, getting them out seemed almost impossible.

So during the 1961 Swedish Grand Prix weekend (which took place in Kristianstad) Degner organised his family’s escape, with the help of a friend from West Germany who made frequent business trips to East Berlin. The friend smuggled them out in a secret compartment in the boot of a Lincoln Mercury, with Degner relying on the fact that the Stasi spent more time watching him at race weekends abroad than his family at home.

He retired from the Swedish race due to engine failure and then fled to West Germany to reunite with his family before moving to Hamamatsu, where Suzuki’s headquarters were located. MZ immediately cancelled their overseas race programme, just in case anyone else had the bright idea of following Degner’s example…

Degner raced for Suzuki in 1962; despite living in constant fear of being killed by the Stasi, he still managed to win the first world title in the 50cc class. But the dream turned into a nightmare the following year. At the Japanese Grand Prix in Suzuka he fell from his bike in the place now known as the Degner Curves and, when the fuel tank exploded, he suffered severe burns requiring over 50 skin grafts.

He returned to racing the following year but was dogged by other accidents before retiring for good in 1966. Living with constant pain caused him to slip into morphine addiction: his death in 1983 aged just 51 (when he was living in Tenerife) was officially down to a heart attack, but many thought it was caused by an overdose, while some people believed that the Stasi finally caught up with him.

In any case, Turns 8 and 9 of the Suzuka track are now named after him as a tribute to his contribution to Japanese motorcycling history.

2024 Japanese Grand Prix: Selected Tyres